Bande dessinée: Why do the French love comic books so much?

One in four books sold in France is a 'bande-dessinée' (comic book) - as the world famous Angoulême comic book festival begins, The Local explores France's enduring love affair with this art form.

Each year, thousands of people flock to Angoulême in south west France in late January. The town, normally only home to a little over 100,000 inhabitants, almost doubles in size once a year as it transforms into the bande dessinée capital of France.

This year, it will be held from January 25th to 28th, bringing together artists, authors, and comic fans from around the world gather to appreciate bandes dessinées, a hobby enjoyed by almost half of French adults and three-quarters of French children.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary last year, national newspaper Libération published an edition illustrated by bande-dessinée.

✏️ Voici la une du @Libe tout en BD 2023. Découvrez jeudi ce numéro entièrement dessiné, à l'occasion du festival d'Angoulême

Lire : https://t.co/nj2k4mQp7h pic.twitter.com/tJ8SV7CeHm

— Libération (@libe) January 25, 2023

France represents the world's fourth largest comic book market - behind Japan, South Korea and the United States, and according to a 2019 report published by the French ministry of culture, bande dessinée production in France has boomed in recent years - reportedly increasing tenfold since 1996.

In 2021, one book out of four sold in France was a comic book, according to Radio France.

"If you go to any FNAC in France, it would not be a surprise to see an adult sitting on the floor reading a bande dessinée, but I would be very surprised to see that in England", said Dr Matthew Screech, visiting lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University who specialises in French language and French studies and author of Masters of the Ninth Art: Bandes Dessinées and Franco-Belgian Identity.

For the French, bandes dessinées - frequently shortened to just BD (roughly pronounced 'beh deh') - have become an integral part of the artistic and cultural landscape, with museums and government funding dedicated to protecting the tradition.

Bandes dessinée covers everything from humorous and light-hearted reading for kids, action and adventure and more adult fare like introspective autobiographies, avante-garde stories and bande-dessinée versions of classic literature.

The history of French bande dessinée

"Many people suggest French language bandes dessinées trace their origins to Töpffer, a French-Swiss schoolmaster at the end of the 19th century," explained Dr Laurence Grove, a professor of French and Text/Image Studies at the University of Glasgow, expert in bande dessinée, and President of the International Bande Dessinée Society.

Sitting in his office, the walls lined colourful comic books, Grove traced the basic history of French bandes dessinées, beginning with the start of the art form in its modern format in the 19th century to its heyday in the 1930s - 1970s.

"Then in the 1980s and '90s, they changed format again," said Grove. "And it was in the '80s and the '90s where the change of format also led to a change of style, and people began publishing bandes dessinées that were not just made for kids".

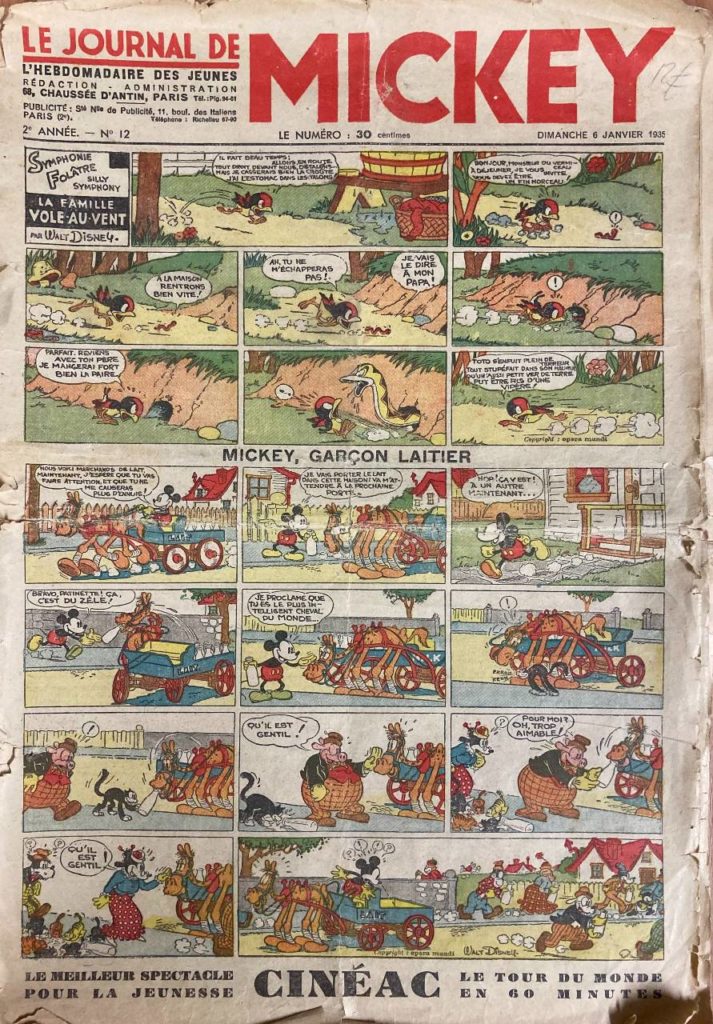

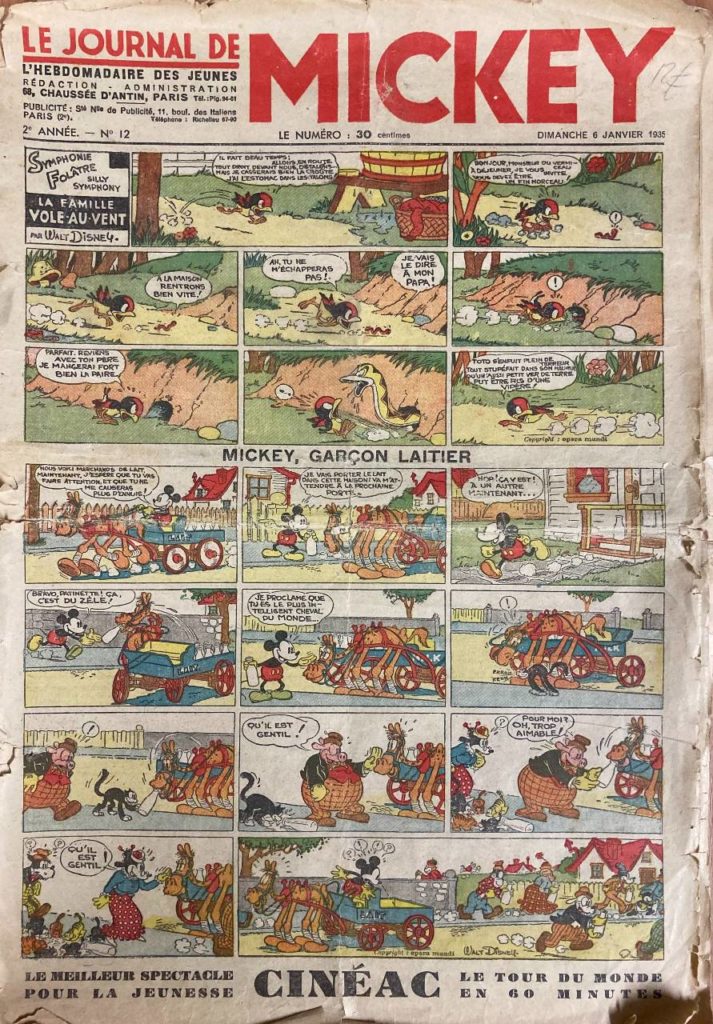

The comics expert said that there were several important moments for bandes dessinées, starting with the Journal du Mickey - which was first published in 1934 in France. It was a collection of weekly Disney comic strips that were translated into French and equipped French references and advertisements.

The Journal de Mickey in 1935 (Photo Credit: Laurence Grove)

"People may not like to admit it, but French comics have been largely influenced by American comics," he explained.

The animated mouse was featured in a weekly French-language children's newspaper, which also offered games and other interactive activities. French children could even join the "Club Mickey".

In the decades that followed, as the pioneering bande dessinée Tintin - created by Belgian author Hergé - grew in popularity, France and the rest of Europe were thrust into war. During this time, comics were used for various partisan and propaganda purposes.

This trend continued in the post-war period, where certain comics were funded by the Communist party - like Vaillant (the precursor to 'Pif'), and others, like the Cœurs vaillants were sponsored by right-leaning, Catholic interest groups.

The Communist party sponsored "Vaillant" comic (L) and the Catholic interest group sponsored series "Coeurs Vaillents" (R) side by side. (Photo Credit: Laurence Grove)

"A whole generation of French kids grew up reading these without realising there was an underlying political agenda," the professor added.

The rise of Tintin

One French-language bande dessinée sticks out as having had a particularly strong impact for generations of comic readers: Tintin (pronounced tahn-tahn in French) which has sold over 200 million copies since its inception and has been translated into over 70 languages.

Dr Screech, the author of The Ninth Art, points to Tintin as the breakthrough moment for bandes dessinées.

"It appealed to children, but it also broke through to the adult market," Dr Screech said.

"There was a whole generation of people who started reading it as a children's comic in the 1930s, and kept reading as it became more sophisticated as time went on. By the time you get to the 1950s, you have complex artwork and storytelling."

For Dr Screech, a large part of the fascination with bandes dessinées in France has to do with the country's literary culture: "I think the culture in France remains more written - a book-based culture. But in England, its music and you could see that with the Beatles. If you want a comparison, you could say Hergé was like the Beatles or Presley for the francophone world".

Becoming a serious art-form

Bandes dessinées - like other art forms - went through several different waves: the first held on until the 1960s and featured comics like the Journal de Mickey. The second wave, according to Dr Screech, began around the 1970s and was marked by an avant-garde and modernist edge, reflecting literary movements occurring in France.

"Until the '80s and '90s, it was the norm was for these comics to be published weekly with a cliffhanger ending", Dr Grove pointed out.

Asterix, the comic book series about a village of Gaulish warriors who go on adventures across the world, was first released in 1959. "Originally it was published a page at a time and then it would be published in an album format", Dr Grove said, noting the evolution in format from single pages to larger, full-album collections.

This helped to bring about the real change for bandes dessinées which came in the 1980s and 90s, as more long-form, graphic novels, with adult themes came onto the market.

Dr Grove pointed to an autobiographical comic series by Fabrice Neaud titled Journal which dove into the experience of being a gay man in a small French town, and not shying away from depictions of sexual activity, which had previously been discouraged in bande dessinée.

Government help

Part of the success and national recognition given to bandes dessinées in France can be attributed to the institutional support that the art form receives from the French government - in common with other art forms like cinema, theatre and literature.

In 1974, the Angoulême International Comics Festival was launched. For almost half a century, the four-day festival has awarded prizes in cartooning, along with a "Grand Prize" that honours a comic creator and makes them the president of the festival for the following year.

The event is well-attended by French government officials, and in 2019, former culture minister Franck Riester gave a speech likening the comic festival to that of the Cannes Film Festival.

France's ministry of Culture was heavily involved in the creation of the Cité Internationale de la Bande dessinée et de l'Image in Angouleme which now includes a museum, a heritage library, a specialised public library, a book shop, documentation centre and an international artists’ residence (la maison des auteurs).

"There is still this notion in the English speaking world that [comics] are a bit of a bastard form you could say - combining pictures with images - neither one form or another, that does not seem to be so much the case in France", Dr Screech explained.

Over the past three decades, French bande dessinée readership has steadily grown.

In 2021, France instituted a "Pass Culture" - Culture Pass - to help give young people more access and funds for cultural activities. While the pass allowed teenagers to access museums and historic cinemas, over time it came to be nicknamed the "Manga Pass" as the €300 'culture' stipend awarded to French teens aged 15 to 18 accounted for a six percent increase in sales of Japanese manga comics across the country.

Comments

See Also

Each year, thousands of people flock to Angoulême in south west France in late January. The town, normally only home to a little over 100,000 inhabitants, almost doubles in size once a year as it transforms into the bande dessinée capital of France.

This year, it will be held from January 25th to 28th, bringing together artists, authors, and comic fans from around the world gather to appreciate bandes dessinées, a hobby enjoyed by almost half of French adults and three-quarters of French children.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary last year, national newspaper Libération published an edition illustrated by bande-dessinée.

✏️ Voici la une du @Libe tout en BD 2023. Découvrez jeudi ce numéro entièrement dessiné, à l'occasion du festival d'Angoulême

— Libération (@libe) January 25, 2023

Lire : https://t.co/nj2k4mQp7h pic.twitter.com/tJ8SV7CeHm

France represents the world's fourth largest comic book market - behind Japan, South Korea and the United States, and according to a 2019 report published by the French ministry of culture, bande dessinée production in France has boomed in recent years - reportedly increasing tenfold since 1996.

In 2021, one book out of four sold in France was a comic book, according to Radio France.

"If you go to any FNAC in France, it would not be a surprise to see an adult sitting on the floor reading a bande dessinée, but I would be very surprised to see that in England", said Dr Matthew Screech, visiting lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University who specialises in French language and French studies and author of Masters of the Ninth Art: Bandes Dessinées and Franco-Belgian Identity.

For the French, bandes dessinées - frequently shortened to just BD (roughly pronounced 'beh deh') - have become an integral part of the artistic and cultural landscape, with museums and government funding dedicated to protecting the tradition.

Bandes dessinée covers everything from humorous and light-hearted reading for kids, action and adventure and more adult fare like introspective autobiographies, avante-garde stories and bande-dessinée versions of classic literature.

The history of French bande dessinée

"Many people suggest French language bandes dessinées trace their origins to Töpffer, a French-Swiss schoolmaster at the end of the 19th century," explained Dr Laurence Grove, a professor of French and Text/Image Studies at the University of Glasgow, expert in bande dessinée, and President of the International Bande Dessinée Society.

Sitting in his office, the walls lined colourful comic books, Grove traced the basic history of French bandes dessinées, beginning with the start of the art form in its modern format in the 19th century to its heyday in the 1930s - 1970s.

"Then in the 1980s and '90s, they changed format again," said Grove. "And it was in the '80s and the '90s where the change of format also led to a change of style, and people began publishing bandes dessinées that were not just made for kids".

The comics expert said that there were several important moments for bandes dessinées, starting with the Journal du Mickey - which was first published in 1934 in France. It was a collection of weekly Disney comic strips that were translated into French and equipped French references and advertisements.

"People may not like to admit it, but French comics have been largely influenced by American comics," he explained.

The animated mouse was featured in a weekly French-language children's newspaper, which also offered games and other interactive activities. French children could even join the "Club Mickey".

In the decades that followed, as the pioneering bande dessinée Tintin - created by Belgian author Hergé - grew in popularity, France and the rest of Europe were thrust into war. During this time, comics were used for various partisan and propaganda purposes.

This trend continued in the post-war period, where certain comics were funded by the Communist party - like Vaillant (the precursor to 'Pif'), and others, like the Cœurs vaillants were sponsored by right-leaning, Catholic interest groups.

"A whole generation of French kids grew up reading these without realising there was an underlying political agenda," the professor added.

The rise of Tintin

One French-language bande dessinée sticks out as having had a particularly strong impact for generations of comic readers: Tintin (pronounced tahn-tahn in French) which has sold over 200 million copies since its inception and has been translated into over 70 languages.

Dr Screech, the author of The Ninth Art, points to Tintin as the breakthrough moment for bandes dessinées.

"It appealed to children, but it also broke through to the adult market," Dr Screech said.

"There was a whole generation of people who started reading it as a children's comic in the 1930s, and kept reading as it became more sophisticated as time went on. By the time you get to the 1950s, you have complex artwork and storytelling."

For Dr Screech, a large part of the fascination with bandes dessinées in France has to do with the country's literary culture: "I think the culture in France remains more written - a book-based culture. But in England, its music and you could see that with the Beatles. If you want a comparison, you could say Hergé was like the Beatles or Presley for the francophone world".

Becoming a serious art-form

Bandes dessinées - like other art forms - went through several different waves: the first held on until the 1960s and featured comics like the Journal de Mickey. The second wave, according to Dr Screech, began around the 1970s and was marked by an avant-garde and modernist edge, reflecting literary movements occurring in France.

"Until the '80s and '90s, it was the norm was for these comics to be published weekly with a cliffhanger ending", Dr Grove pointed out.

Asterix, the comic book series about a village of Gaulish warriors who go on adventures across the world, was first released in 1959. "Originally it was published a page at a time and then it would be published in an album format", Dr Grove said, noting the evolution in format from single pages to larger, full-album collections.

This helped to bring about the real change for bandes dessinées which came in the 1980s and 90s, as more long-form, graphic novels, with adult themes came onto the market.

Dr Grove pointed to an autobiographical comic series by Fabrice Neaud titled Journal which dove into the experience of being a gay man in a small French town, and not shying away from depictions of sexual activity, which had previously been discouraged in bande dessinée.

Government help

Part of the success and national recognition given to bandes dessinées in France can be attributed to the institutional support that the art form receives from the French government - in common with other art forms like cinema, theatre and literature.

In 1974, the Angoulême International Comics Festival was launched. For almost half a century, the four-day festival has awarded prizes in cartooning, along with a "Grand Prize" that honours a comic creator and makes them the president of the festival for the following year.

The event is well-attended by French government officials, and in 2019, former culture minister Franck Riester gave a speech likening the comic festival to that of the Cannes Film Festival.

France's ministry of Culture was heavily involved in the creation of the Cité Internationale de la Bande dessinée et de l'Image in Angouleme which now includes a museum, a heritage library, a specialised public library, a book shop, documentation centre and an international artists’ residence (la maison des auteurs).

"There is still this notion in the English speaking world that [comics] are a bit of a bastard form you could say - combining pictures with images - neither one form or another, that does not seem to be so much the case in France", Dr Screech explained.

Over the past three decades, French bande dessinée readership has steadily grown.

In 2021, France instituted a "Pass Culture" - Culture Pass - to help give young people more access and funds for cultural activities. While the pass allowed teenagers to access museums and historic cinemas, over time it came to be nicknamed the "Manga Pass" as the €300 'culture' stipend awarded to French teens aged 15 to 18 accounted for a six percent increase in sales of Japanese manga comics across the country.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.