OPINION: France's 'slow train' revolution may just be the future for travel

Famous for its high-speed TGV trains, France is now seeing the launch of a new rail revolution - slow trains. John Lichfield looks at the ambitious plan to reconnect some of France's forgotten areas through a rail co-operative and a new philosophy of rail travel.

France, the home of the Very Fast Train, is about to rediscover the Slow Train.

From the end of this year, a new railway company, actually a cooperative, will offer affordable, long-distance travel between provincial towns and cities. The new trains – Trains à Grande Lenteur (TGL)?– will wander for hours along unused, or under-used, secondary lines.

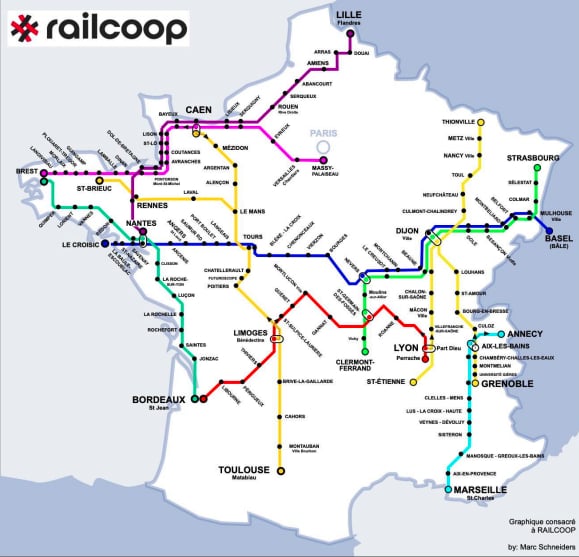

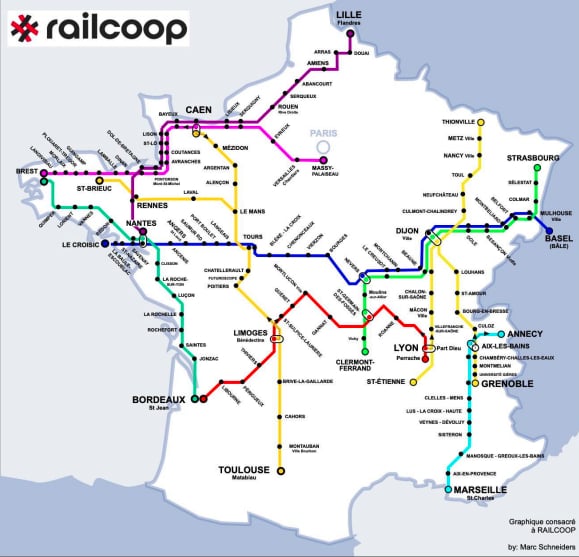

The first service will be from Bordeaux to Lyon, zig-zagging across the broad waist of France through Libourne, Périgueux, Limoges, Guéret, Montluçon and Roanne. Journey time: seven hours and 30 minutes.

Other itineraries will eventually include: Caen to Toulouse, via Limoges in nine hours and 43 minutes and Le Croisic, in Brittany, to Basel in Switzerland, with 25 intermediate stops in 11 hours and 13 minutes.

To a railway lover like me such meandering journeys through La France Profonde sound marvellous. Can they possibly be a commercial proposition?

Some of the services, like Bordeaux-Lyon, were abandoned by the state railway company, the SNCF, several years ago. Others will be unbroken train journeys avoiding Paris which have never existed before - not even at the height of French railway boom at the end of the 19th century.

The venture has been made possible by the EU-inspired scrapping of SNCF’s monopoly on French rail passenger services. The Italian rail company Trenitalia is already competing on the high-speed TGV line between Lyon and Paris.

The low-speed trains also grow from an initiative by President Emmanuel Macron and his government to rescue some of France’s under-used, 19th century, local railways - a reversal of the policy adopted in Britain under Dr Richard Beeching from 1963.

The cross-country, slow train idea was formally approved by the rail regulator before Christmas. It has been developed by French public interest company called Railcoop (pronounced Rye-cope), which has already started its own freight service in south west France.

Ticket prices are still being calculated but they are forecast to be similar to the cost of “ride-sharing” on apps like BlaBla Car.

A little research shows that a Caen-Toulouse ticket might therefore be circa €30 for an almost ten-hour journey. SNCF currently demands between €50 and €90 for a seven-and-a-half-hour trip, including crossing Paris by Metro between Gares Saint Lazare and Montparnasse.

Maybe Railcoop is onto something after all.

The company/cooperative has over 11,000 members or “share-holders”, ranging from local authorities, businesses, pressure groups, railwaymen and women to future passengers. The minimum contribution for an individual is €100.

The plan is to reconnect towns ignored, or poorly served, by the Train à Grande Vitesse (TGV) high speed train revolution in France of the last 40 years. Parts of the Bordeaux-Lyon route are already covered by local passenger trains; other parts are now freight only.

In the longer term, Railcoop foresees long-distance night trains; local trains on abandoned routes; and more freight trains. It promises “new technological” solutions, such as “clean” hydrogen-powered trains.

MAP France's planned new night trains

For the time being it plans to lease and rebuild eight three carriage, diesel trains which have been made redundant in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region.

There will be no space for a buffet or restaurant car. Restaurants and shops along the route will be invited to prepare local specialities which will be sold during station stops and eaten on board.

What a wonderful idea: French provincial meals on wheels; traiteurs on trains.

Olivia Wolanin of Railcoop told me: “We want to be part of the transition to a greener future, which is inevitably going to mean more train travel.

“We also want to offer journeys at a reasonable price to people who live in or want to visit parts of France where train services have all but vanished. We see ourselves as a service for people who have no cars - but also for people who DO have cars.”

Full disclosure. I am a fan of railways. I spent much of my childhood at Crewe station in Cheshire closely observing trains.

Three years ago I wrote a column for The Local on the dilemma facing SNCF and the French government on the 9,000 kilometres of underused and under-maintained local railway lines in France. Something like half had been reduced to low speeds because the track was so unreliable. Several dozen lines had been “suspended” but not yet officially axed.

The government commissioned senior civil servant, and rail-lover, François Philizot to study the problem. After many delays, he reported that much of the French rail network was in a state of “collapse”. Far from turning out to be a French Beeching, he recommended that a few lines might have to close but most could and should be saved – either by national government or by regional governments.

Since then the Emmanuel Macron-Jean Castex government has promised a big new chunk of spending on “small lines” as part of its €100 billion three year Covid-recovery plan. Even more spending is needed but, for the first time since the TGV revolution began in 1981, big sums are to be spent on old lines in France as well as new ones.

The Railcoop cross-country network, to be completed by 2024-5, will run (at an average of 90 kph) partly on those tracks. Can it succeed where a similar German scheme failed?

François Philizot suggested in a recent interview with Le Monde that a revival of slow trains might work - so long as we accept that a greener future will also be a less frenetic future.

“When you’re not shooting across the country like an arrow at 300 kph, you can see much more and you can think for much longer,” Philizot said.

Amen to that.

Comments (8)

See Also

France, the home of the Very Fast Train, is about to rediscover the Slow Train.

From the end of this year, a new railway company, actually a cooperative, will offer affordable, long-distance travel between provincial towns and cities. The new trains – Trains à Grande Lenteur (TGL)?– will wander for hours along unused, or under-used, secondary lines.

The first service will be from Bordeaux to Lyon, zig-zagging across the broad waist of France through Libourne, Périgueux, Limoges, Guéret, Montluçon and Roanne. Journey time: seven hours and 30 minutes.

Other itineraries will eventually include: Caen to Toulouse, via Limoges in nine hours and 43 minutes and Le Croisic, in Brittany, to Basel in Switzerland, with 25 intermediate stops in 11 hours and 13 minutes.

To a railway lover like me such meandering journeys through La France Profonde sound marvellous. Can they possibly be a commercial proposition?

Some of the services, like Bordeaux-Lyon, were abandoned by the state railway company, the SNCF, several years ago. Others will be unbroken train journeys avoiding Paris which have never existed before - not even at the height of French railway boom at the end of the 19th century.

The venture has been made possible by the EU-inspired scrapping of SNCF’s monopoly on French rail passenger services. The Italian rail company Trenitalia is already competing on the high-speed TGV line between Lyon and Paris.

The low-speed trains also grow from an initiative by President Emmanuel Macron and his government to rescue some of France’s under-used, 19th century, local railways - a reversal of the policy adopted in Britain under Dr Richard Beeching from 1963.

The cross-country, slow train idea was formally approved by the rail regulator before Christmas. It has been developed by French public interest company called Railcoop (pronounced Rye-cope), which has already started its own freight service in south west France.

Ticket prices are still being calculated but they are forecast to be similar to the cost of “ride-sharing” on apps like BlaBla Car.

A little research shows that a Caen-Toulouse ticket might therefore be circa €30 for an almost ten-hour journey. SNCF currently demands between €50 and €90 for a seven-and-a-half-hour trip, including crossing Paris by Metro between Gares Saint Lazare and Montparnasse.

Maybe Railcoop is onto something after all.

The company/cooperative has over 11,000 members or “share-holders”, ranging from local authorities, businesses, pressure groups, railwaymen and women to future passengers. The minimum contribution for an individual is €100.

The plan is to reconnect towns ignored, or poorly served, by the Train à Grande Vitesse (TGV) high speed train revolution in France of the last 40 years. Parts of the Bordeaux-Lyon route are already covered by local passenger trains; other parts are now freight only.

In the longer term, Railcoop foresees long-distance night trains; local trains on abandoned routes; and more freight trains. It promises “new technological” solutions, such as “clean” hydrogen-powered trains.

MAP France's planned new night trains

For the time being it plans to lease and rebuild eight three carriage, diesel trains which have been made redundant in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region.

There will be no space for a buffet or restaurant car. Restaurants and shops along the route will be invited to prepare local specialities which will be sold during station stops and eaten on board.

What a wonderful idea: French provincial meals on wheels; traiteurs on trains.

Olivia Wolanin of Railcoop told me: “We want to be part of the transition to a greener future, which is inevitably going to mean more train travel.

“We also want to offer journeys at a reasonable price to people who live in or want to visit parts of France where train services have all but vanished. We see ourselves as a service for people who have no cars - but also for people who DO have cars.”

Full disclosure. I am a fan of railways. I spent much of my childhood at Crewe station in Cheshire closely observing trains.

Three years ago I wrote a column for The Local on the dilemma facing SNCF and the French government on the 9,000 kilometres of underused and under-maintained local railway lines in France. Something like half had been reduced to low speeds because the track was so unreliable. Several dozen lines had been “suspended” but not yet officially axed.

The government commissioned senior civil servant, and rail-lover, François Philizot to study the problem. After many delays, he reported that much of the French rail network was in a state of “collapse”. Far from turning out to be a French Beeching, he recommended that a few lines might have to close but most could and should be saved – either by national government or by regional governments.

Since then the Emmanuel Macron-Jean Castex government has promised a big new chunk of spending on “small lines” as part of its €100 billion three year Covid-recovery plan. Even more spending is needed but, for the first time since the TGV revolution began in 1981, big sums are to be spent on old lines in France as well as new ones.

The Railcoop cross-country network, to be completed by 2024-5, will run (at an average of 90 kph) partly on those tracks. Can it succeed where a similar German scheme failed?

François Philizot suggested in a recent interview with Le Monde that a revival of slow trains might work - so long as we accept that a greener future will also be a less frenetic future.

“When you’re not shooting across the country like an arrow at 300 kph, you can see much more and you can think for much longer,” Philizot said.

Amen to that.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.