What is France doing to prevent 'illegal' Channel crossings to UK?

When 31 people died after their small boat sank off the coast of northern France in November 2021, there were hopes that the tragedy would push the British and French governments into working together to stop the highly dangerous crossings. But, one year on, the problem as bad than ever.

Hopes of cross-border co-operation between the British and French quickly faded in the face of repeated wars of words, although the latest British PM Rishi Sunak said after his first call with French president Emmanuel Macron that the pair had agreed to work together on the issue.

What the past year has mostly seen instead is a blame game - with the British saying that they French are not doing enough to police their northern coastline, while the French blame the British asylum system.

So have the French been doing enough to prevent people setting off in small boats?

What's clear is that French authorities, police and border officers face an unprecedented and ever-worsening problem.

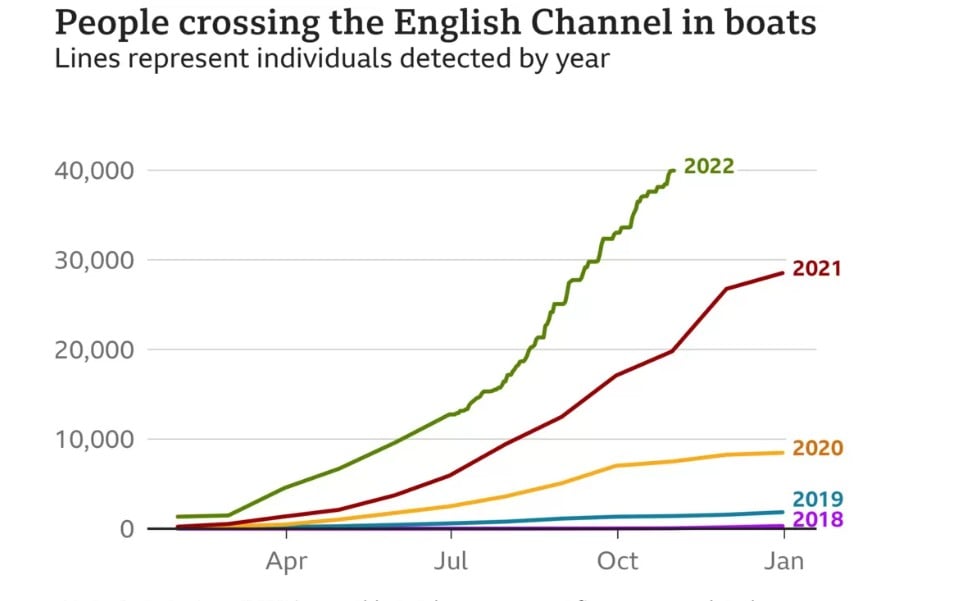

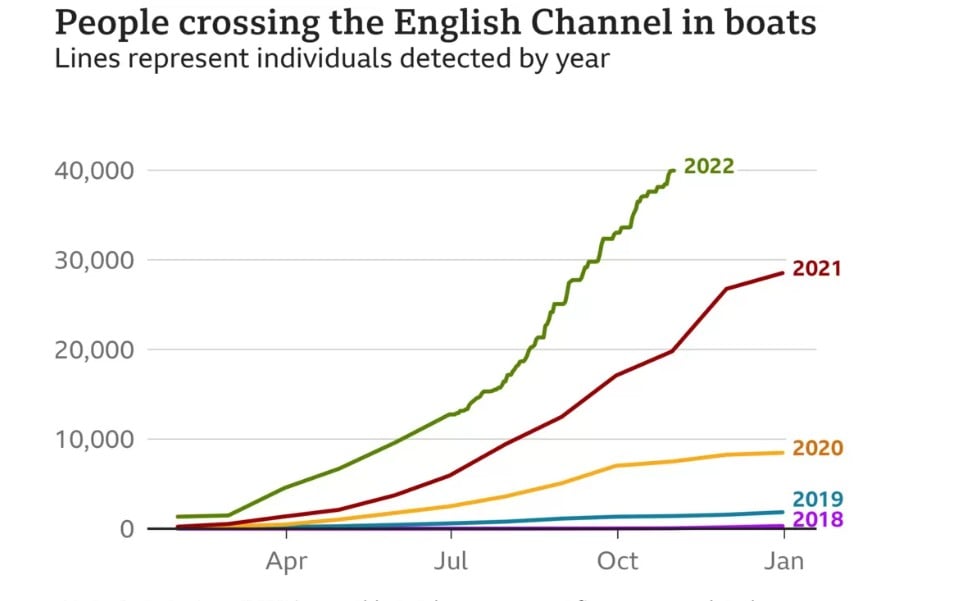

On peak days up to 1,000 people arrive on UK shores, crossing the Channel on small boats and makeshift rafts and in total the crossings have more than doubled in 2022.

So far in 2022, almost 40,000 people have reached the UK in small boat crossings - and a further 30,000 have been intercepted in France.

As part of an agreement with the UK government, France has doubled the number of police officers patrolling the northern shores.

Why is there such a big increase in boat crossings?

Arrivals by boat have undoubtedly increased markedly in recent years, up from 8,000 people in 2018 to 28,000 in 2021 and 40,000 so far this year.

Data from UK Home Office/Ministry of Defence. Graphic: BBC News

But total arrivals in the UK may not have increased at all - the difference is in how people arrive.

Since 2018 British and French authorities have greatly tightened security at ports and stations so that other methods of arrival - for example in the back of lorries or smuggled in vans - are now virtually impossible, while passport checks have also been tightened.

This, coupled with the UK's closing of routes to seek asylum from abroad, means that many people without valid passports or visas now have only one option to enter the UK - making the highly dangerous Channel crossing by small boat.

The other difference is that people arriving by small boat virtually all end up in the hands of UK authorities, whereas people who arrived smuggled by lorry often escaped detection altogether, so the recent numbers seems bigger.

Accurate data is hard to come by when we're talking about illicit and "illegal" arrivals - but if we look at the number of people who claim asylum in the UK, that number was 48,000 in 2021. That represents a significant increase compared to the previous 10 years, but is just over half the rate of applications in 2002 (84,000).

The 'historic' agreement

In July 2021, French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin heralded a 'historic' agreement signed with the UK. In return for €63 million of UK funding, France promised the following:

- to double the number of police and gendarmes patrolling along the French coastline;

- to finance border protection and surveillance equipment;

- to detect and intercept migrants attempting to cross the Channel;

- and to fight against human trafficking.

Following the signing of the deal with the UK, France now employs between 600-650 police officers, gendarmes and customs agents to patrol its northern coastline - a marked increase.

Despite a spat over whether the UK had actually paid what it promised, the French operation has increased its effectiveness in detaining people setting out on crossings.

Figures published by the French Senate back in 2021 showed 10,000 arrests made between August 2020 and August 2021.

The table below shows the number of successful crossings (traversées) made between 2019 and 2021 compared to the number of failed crossings (Tentatives). The figures also revealed France had arrested or intercepted 10,522 undocumented migrants whilst 12,256 were picked up by police in the UK.

By 2022, the arrest figure had risen to 30,000.

The Senate report also said: "France considers that it is doing its maximum to monitor its coast. During its hearing, the Directorate-General for Foreigners in France (DGEF) underlined that this effort had cost France €217 million."

Who are the people in the boats?

They're often referred to as migrants, but of the people who make it to the UK, almost all (93 percent) apply for asylum - roughly half are granted asylum at the first attempt, a figure that rises to 70 percent when successful appeals against asylum refusal are taken into account.

Crossings in 2022 have seen a sharp rise in Albanians, while other arrivals are from Afghanistan, Iran, Syria and Eritrea.

The crossings are arranged by organised gangs of people smugglers who work across France, Belgium and the Netherlands and charge up to €3,500 for a place in a boat. One aspect that adds to the challenge for French authorities is that many people who attempt the crossing are only in France for a matter of hours - transported by the gangs from Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands to make the crossing.

French authorities believe that disrupting the people smuggling gangs is the most effective way to end the crossings, and are working on a Europol level on this.

French police and coastguard say they face a difficult task trying to monitor hundreds of kilometres of rugged coastline with limited resources, while people smuggling networks are growing more sophisticated.

The French have a policy of not intercepting boats once they are in the water, judging any attempt to stop the dinghies too dangerous because of the risk of panic or sudden movements that could capsize the vessels.

Humanitarian crisis

But Pierre Roques, manager of Auberge des Migrants, an NGO that has been working with migrants in northern France since 2008, current attempts by both the French and the British are simply making things worse.

"It is very difficult for the police to stop people from crossing. We are talking about 150km of coastline, not a port," he said. "The more money the UK gives to France to militarise the border, the more migrants will turn to traffickers to try to make it across - because they have no legitimate way of doing so."

"We are facing a humanitarian crisis and need a humanitarian solution - not a military one," Roques continued.

What next?

It's clear that policing - both of the people-smuggling gangs and the crossings themselves - can only ever be part of the solution, so what else is proposed?

The UK government launched a policy to send small boat arrivals to Rwanda, although this policy has not yet been put into effect due to legal challenges and the airline chartered to take the first aborted flight has said it will not attempt any more. The government had hoped this would have a deterrent effect on people coming to the UK, but there has been no noticeable falls in arrivals since it was announced in May 2022.

The French government has said that the British government's decisiong to close many legal routes for people to apply for asylum from outside the UK is at least part of the problem, leaving them with little choice but to risk their lives in the Channel. They also claim that the lack of ID cards in the UK acts as a draw to people who believe it is easier to work illegally. The UK government rejects both these points.

The other point of contention is the Le Touquet agreement - a 2004 agreement over border control between France and the UK that allows for reciprocal border controls of French and UK officials in each other’s countries. It's why French passport control officers work in Dover or at London St Pancras station and British passport control officers can be seen in French ports including Calais and at Gare du Nord.

READ ALSO What is the Le Touquet agreement and why do some French politicians want to scrap it?

It's this treaty that makes the small boat arrivals in the UK a French problem, and there are some in France who would like to see it scrapped.

The current French government has made no such calls, but does want the UK to set up an asylum processing centre in northern France - so that people who want to apply for asylum in the UK can have their claims processed in France, and then make the crossing legally and safely if they are granted asylum. The British have rejected this idea.

Macron and Sunak have announced a bilateral summit on UK-French co-operation, including on Channel crossings, for 2023.

Why don't they stay in France?

The question that always pops up when the UK media talks about arrivals from France is - why don't they stay in France, since France is a safe country?

In general people travel to the UK either because they already speak some English, or they have family connections in the UK or both. There is also some suggestion that the lack of ID cards in the UK means it will be easier to work illegally, although this isn't really borne out by facts: France has a large number of illegal 'sans papiers' workers too.

As mentioned, many of those who arrive on boats enter France only in order to make the crossing to the UK and have no interest in staying in France - usually because they don't speak French and have no family or connections in France.

But any suggestion that France is dodging its responsibilities are wide of the mark - the UK has one of the lowest number of asylum applications per year in Europe - 48,000 in 2021, compared to 120,000 in France and 190,000 in Germany.

Comments (7)

See Also

Hopes of cross-border co-operation between the British and French quickly faded in the face of repeated wars of words, although the latest British PM Rishi Sunak said after his first call with French president Emmanuel Macron that the pair had agreed to work together on the issue.

What the past year has mostly seen instead is a blame game - with the British saying that they French are not doing enough to police their northern coastline, while the French blame the British asylum system.

So have the French been doing enough to prevent people setting off in small boats?

What's clear is that French authorities, police and border officers face an unprecedented and ever-worsening problem.

On peak days up to 1,000 people arrive on UK shores, crossing the Channel on small boats and makeshift rafts and in total the crossings have more than doubled in 2022.

So far in 2022, almost 40,000 people have reached the UK in small boat crossings - and a further 30,000 have been intercepted in France.

As part of an agreement with the UK government, France has doubled the number of police officers patrolling the northern shores.

Why is there such a big increase in boat crossings?

Arrivals by boat have undoubtedly increased markedly in recent years, up from 8,000 people in 2018 to 28,000 in 2021 and 40,000 so far this year.

But total arrivals in the UK may not have increased at all - the difference is in how people arrive.

Since 2018 British and French authorities have greatly tightened security at ports and stations so that other methods of arrival - for example in the back of lorries or smuggled in vans - are now virtually impossible, while passport checks have also been tightened.

This, coupled with the UK's closing of routes to seek asylum from abroad, means that many people without valid passports or visas now have only one option to enter the UK - making the highly dangerous Channel crossing by small boat.

The other difference is that people arriving by small boat virtually all end up in the hands of UK authorities, whereas people who arrived smuggled by lorry often escaped detection altogether, so the recent numbers seems bigger.

Accurate data is hard to come by when we're talking about illicit and "illegal" arrivals - but if we look at the number of people who claim asylum in the UK, that number was 48,000 in 2021. That represents a significant increase compared to the previous 10 years, but is just over half the rate of applications in 2002 (84,000).

The 'historic' agreement

In July 2021, French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin heralded a 'historic' agreement signed with the UK. In return for €63 million of UK funding, France promised the following:

- to double the number of police and gendarmes patrolling along the French coastline;

- to finance border protection and surveillance equipment;

- to detect and intercept migrants attempting to cross the Channel;

- and to fight against human trafficking.

Following the signing of the deal with the UK, France now employs between 600-650 police officers, gendarmes and customs agents to patrol its northern coastline - a marked increase.

Despite a spat over whether the UK had actually paid what it promised, the French operation has increased its effectiveness in detaining people setting out on crossings.

Figures published by the French Senate back in 2021 showed 10,000 arrests made between August 2020 and August 2021.

The table below shows the number of successful crossings (traversées) made between 2019 and 2021 compared to the number of failed crossings (Tentatives). The figures also revealed France had arrested or intercepted 10,522 undocumented migrants whilst 12,256 were picked up by police in the UK.

By 2022, the arrest figure had risen to 30,000.

The Senate report also said: "France considers that it is doing its maximum to monitor its coast. During its hearing, the Directorate-General for Foreigners in France (DGEF) underlined that this effort had cost France €217 million."

Who are the people in the boats?

They're often referred to as migrants, but of the people who make it to the UK, almost all (93 percent) apply for asylum - roughly half are granted asylum at the first attempt, a figure that rises to 70 percent when successful appeals against asylum refusal are taken into account.

Crossings in 2022 have seen a sharp rise in Albanians, while other arrivals are from Afghanistan, Iran, Syria and Eritrea.

The crossings are arranged by organised gangs of people smugglers who work across France, Belgium and the Netherlands and charge up to €3,500 for a place in a boat. One aspect that adds to the challenge for French authorities is that many people who attempt the crossing are only in France for a matter of hours - transported by the gangs from Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands to make the crossing.

French authorities believe that disrupting the people smuggling gangs is the most effective way to end the crossings, and are working on a Europol level on this.

French police and coastguard say they face a difficult task trying to monitor hundreds of kilometres of rugged coastline with limited resources, while people smuggling networks are growing more sophisticated.

The French have a policy of not intercepting boats once they are in the water, judging any attempt to stop the dinghies too dangerous because of the risk of panic or sudden movements that could capsize the vessels.

Humanitarian crisis

But Pierre Roques, manager of Auberge des Migrants, an NGO that has been working with migrants in northern France since 2008, current attempts by both the French and the British are simply making things worse.

"It is very difficult for the police to stop people from crossing. We are talking about 150km of coastline, not a port," he said. "The more money the UK gives to France to militarise the border, the more migrants will turn to traffickers to try to make it across - because they have no legitimate way of doing so."

"We are facing a humanitarian crisis and need a humanitarian solution - not a military one," Roques continued.

What next?

It's clear that policing - both of the people-smuggling gangs and the crossings themselves - can only ever be part of the solution, so what else is proposed?

The UK government launched a policy to send small boat arrivals to Rwanda, although this policy has not yet been put into effect due to legal challenges and the airline chartered to take the first aborted flight has said it will not attempt any more. The government had hoped this would have a deterrent effect on people coming to the UK, but there has been no noticeable falls in arrivals since it was announced in May 2022.

The French government has said that the British government's decisiong to close many legal routes for people to apply for asylum from outside the UK is at least part of the problem, leaving them with little choice but to risk their lives in the Channel. They also claim that the lack of ID cards in the UK acts as a draw to people who believe it is easier to work illegally. The UK government rejects both these points.

The other point of contention is the Le Touquet agreement - a 2004 agreement over border control between France and the UK that allows for reciprocal border controls of French and UK officials in each other’s countries. It's why French passport control officers work in Dover or at London St Pancras station and British passport control officers can be seen in French ports including Calais and at Gare du Nord.

READ ALSO What is the Le Touquet agreement and why do some French politicians want to scrap it?

It's this treaty that makes the small boat arrivals in the UK a French problem, and there are some in France who would like to see it scrapped.

The current French government has made no such calls, but does want the UK to set up an asylum processing centre in northern France - so that people who want to apply for asylum in the UK can have their claims processed in France, and then make the crossing legally and safely if they are granted asylum. The British have rejected this idea.

Macron and Sunak have announced a bilateral summit on UK-French co-operation, including on Channel crossings, for 2023.

Why don't they stay in France?

The question that always pops up when the UK media talks about arrivals from France is - why don't they stay in France, since France is a safe country?

In general people travel to the UK either because they already speak some English, or they have family connections in the UK or both. There is also some suggestion that the lack of ID cards in the UK means it will be easier to work illegally, although this isn't really borne out by facts: France has a large number of illegal 'sans papiers' workers too.

As mentioned, many of those who arrive on boats enter France only in order to make the crossing to the UK and have no interest in staying in France - usually because they don't speak French and have no family or connections in France.

But any suggestion that France is dodging its responsibilities are wide of the mark - the UK has one of the lowest number of asylum applications per year in Europe - 48,000 in 2021, compared to 120,000 in France and 190,000 in Germany.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.