OPINION: Who are really the rudest - the French, tourists or Parisians?

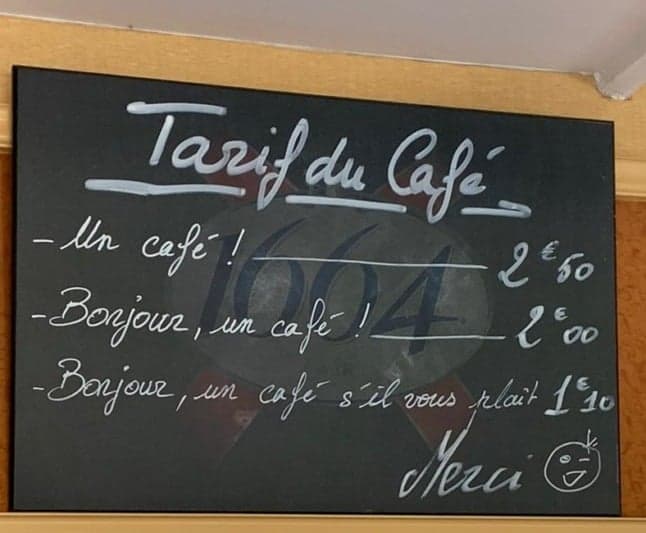

What is the price of rudeness? Between 90 centimes and €1.40, according to a sign in a café close to my home in the beautiful hills of Calvados.

A couple of days ago, I tweeted a picture of a sign in the café-brasserie-PMU-tabac in Clécy, 45 kilometres south of Caen.

The sign read:

Tarif du café.

Un café! 2€50.

Bonjour, un café! 2€.

Bonjour un café, s’il vous plaît 1€10.

(Coffee prices - A coffee €2.50, Hello, a coffee €2, Hello, a coffee please €1.10)

The price of everyday rudeness. Seen in a Café in Clécy, Calvados. I wonder if they sell any at € 1.10. pic.twitter.com/dSYmb63SGr

— John Lichfield (@john_lichfield) September 7, 2021

The tweet went viral. It has, so far, gained 400 retweets and more than 2,800 'likes', including reactions from people all over the world.

The sign is not entirely original. Similar exhortations to good manners can be found in many French cafés and restaurants.

To foreign visitors French people - and especially Parisians - have a reputation for rudeness which is not entirely undeserved but less deserved than it used to be. The French themselves have codes of everyday politeness which foreigners constantly breach.

READ ALSO The French aren't really rude, it's just a big misunderstanding

Scene, a French railway station. A traveller (me) has 5 minutes to catch his train. I ask a man in a red hat which platform my train is leaving from.

Bonjour, monsieur, says the SNCF customer service official. Then he says nothing until I also say bonjour. I now have 4 minutes 30 seconds to catch the train.

This has happened to me several times. I know, in theory, that all transactions between strangers in France should start with bonjour and end in merci. I always remember the merci. I often forget the bonjour.

EXPLAINED Why bonjour is the most sacred word to French people

This attachment to polite but formal codes of first contact is, I think, linked to France’s constitutional commitment to Egalité. We are all citizens. We should address one another as equals. We should not treat others as servants or minions. Fair enough.

French waiters, and other people in contact with the public, have other ways of asserting this right to be treated equally. Sometimes it can be mistaken by foreigners for rudeness. Sometimes it IS rudeness.

A couple of years ago, in an idle moment, I was sitting on a café terrace on the Champs Elysées in Paris. A group of German tourists arrived and sat down at an uncleared table.

The waiter berated them in French. They replied in English. He said, in French: “In France, we speak French”. They said, in English: “We can’t speak French.

He refused to serve them. The Germans left. One turned to the waiter and said merde. “There you are,” he said with a big smile. “I knew you could speak French.”

Investigative journalism is not dead. I decided to go back to the café in Clécy to find out more about the “cost of rudeness” sign.

Who was the sign aimed at? Locals? Foreigners? Parisians? Did the café owners enforce their “fines” for being impolite?

Remembering to say bonjour and s’il vous plaît, I ordered a coffee. I introduced myself. I showed the patronne my tweet and told her how successful it had been. She was mildly amused that her little, chalked sign had made a virtual tour of the world.

It turned out that she was the grand-daughter of a former mayor of my village eight kilometres away. Clémentine Dubois, 35, has run the bar and PMU (betting shop)in Clécy for two years.

“We put up the sign soon after we started,” she said. “There were some people who came in here who were very abrupt with me. I didn’t think that was right. Manners are important. They are the basis of everything we do together.”

Were the offenders foreign tourists? Or Parisians maybe?

“No, not at all,” Clémentine said. “They were local. Old men mostly. They are very off-hand with me - bossy. I thought the sign would be a good way of reminding them to be polite.”

Does she enforce the price-differential? “No. It’s just a joke… but, you know, I think it has worked. We get very little rudeness now.”

So there you are. The French politeness code is not universally known or respected even by the French - or not the grumpy, old, male, rural French. Several French replies to my tweet pointed out that the requirement that every conversation should begin with bonjour is actually quite new and urban.

In the French countryside, a meeting between neighbours or strangers would once, and not so long ago, have always started with a comment on the weather. Just like in Britain.

How much did I pay for my coffee in the Clécy brasserie-tabac-PMU? Nothing. Clémentine refused my €1.10.

Comments (4)

See Also

A couple of days ago, I tweeted a picture of a sign in the café-brasserie-PMU-tabac in Clécy, 45 kilometres south of Caen.

The sign read:

Tarif du café.

Un café! 2€50.

Bonjour, un café! 2€.

Bonjour un café, s’il vous plaît 1€10.

(Coffee prices - A coffee €2.50, Hello, a coffee €2, Hello, a coffee please €1.10)

The price of everyday rudeness. Seen in a Café in Clécy, Calvados. I wonder if they sell any at € 1.10. pic.twitter.com/dSYmb63SGr

— John Lichfield (@john_lichfield) September 7, 2021

The tweet went viral. It has, so far, gained 400 retweets and more than 2,800 'likes', including reactions from people all over the world.

The sign is not entirely original. Similar exhortations to good manners can be found in many French cafés and restaurants.

To foreign visitors French people - and especially Parisians - have a reputation for rudeness which is not entirely undeserved but less deserved than it used to be. The French themselves have codes of everyday politeness which foreigners constantly breach.

READ ALSO The French aren't really rude, it's just a big misunderstanding

Scene, a French railway station. A traveller (me) has 5 minutes to catch his train. I ask a man in a red hat which platform my train is leaving from.

Bonjour, monsieur, says the SNCF customer service official. Then he says nothing until I also say bonjour. I now have 4 minutes 30 seconds to catch the train.

This has happened to me several times. I know, in theory, that all transactions between strangers in France should start with bonjour and end in merci. I always remember the merci. I often forget the bonjour.

EXPLAINED Why bonjour is the most sacred word to French people

This attachment to polite but formal codes of first contact is, I think, linked to France’s constitutional commitment to Egalité. We are all citizens. We should address one another as equals. We should not treat others as servants or minions. Fair enough.

French waiters, and other people in contact with the public, have other ways of asserting this right to be treated equally. Sometimes it can be mistaken by foreigners for rudeness. Sometimes it IS rudeness.

A couple of years ago, in an idle moment, I was sitting on a café terrace on the Champs Elysées in Paris. A group of German tourists arrived and sat down at an uncleared table.

The waiter berated them in French. They replied in English. He said, in French: “In France, we speak French”. They said, in English: “We can’t speak French.

He refused to serve them. The Germans left. One turned to the waiter and said merde. “There you are,” he said with a big smile. “I knew you could speak French.”

Investigative journalism is not dead. I decided to go back to the café in Clécy to find out more about the “cost of rudeness” sign.

Who was the sign aimed at? Locals? Foreigners? Parisians? Did the café owners enforce their “fines” for being impolite?

Remembering to say bonjour and s’il vous plaît, I ordered a coffee. I introduced myself. I showed the patronne my tweet and told her how successful it had been. She was mildly amused that her little, chalked sign had made a virtual tour of the world.

It turned out that she was the grand-daughter of a former mayor of my village eight kilometres away. Clémentine Dubois, 35, has run the bar and PMU (betting shop)in Clécy for two years.

“We put up the sign soon after we started,” she said. “There were some people who came in here who were very abrupt with me. I didn’t think that was right. Manners are important. They are the basis of everything we do together.”

Were the offenders foreign tourists? Or Parisians maybe?

“No, not at all,” Clémentine said. “They were local. Old men mostly. They are very off-hand with me - bossy. I thought the sign would be a good way of reminding them to be polite.”

Does she enforce the price-differential? “No. It’s just a joke… but, you know, I think it has worked. We get very little rudeness now.”

So there you are. The French politeness code is not universally known or respected even by the French - or not the grumpy, old, male, rural French. Several French replies to my tweet pointed out that the requirement that every conversation should begin with bonjour is actually quite new and urban.

In the French countryside, a meeting between neighbours or strangers would once, and not so long ago, have always started with a comment on the weather. Just like in Britain.

How much did I pay for my coffee in the Clécy brasserie-tabac-PMU? Nothing. Clémentine refused my €1.10.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.